No Language, No Streets

Rick Wester

July 28—September 9, 2017

David Coon, Victoria Crayhon, Jan Cunningham, Kathryn Frund, Joan Gardner, Ken Grimes, Barbara Hocker, Andrew Hogan, Deana Lawson, Elizabeth Livingston, Beth Lovell, Susan McCaslin, Mercedes Teixido.

Guest curator Rick Wester pulls work from the Artspace Flatfile for this exhibition in our Project Room.

Curator Statement:

At the onset, choosing an exhibition of works by artists previously unknown to the curator seems like a dangerous opportunity and maybe even more, a foolhardy challenge, so, of course, it was something I wanted to embrace. No one owns or runs an art gallery in New York based mostly on emerging artists if they get hives from such propositions. Unless, they like scratching.

As an outsider, diving deeply into the flat files at Artspace was like leaping headlong into virgin waters from a craggy cliff. Swimming to the surface, gently exhaling the air held to survive, a world emerges that is different from the one leapt from. What was discovered beneath the surface was a rich and complex world of varied approaches, mediums, concepts and execution.

The show’s title, No Language, No Streets, is a riff on the title of Barbara Hocker’s work, Somewhere without language, or streets, 2017, which in itself is a borrowed quote from Wim Wender’s tragically beautiful film, Paris, Texas. The line comes from a monologue given by the film’s main character, Travis (played by Harry Dean Stanton) as he speaks to his estranged wife, Jane (played by Nastassja Kinski) through the one-way mirror of a peep show booth. The speech, later matched by Jane, is part confession, part folk tale, a cautionary story of the dissolution of a relationship and its aftermath. Hocker’s work, a four-part panorama of images taken while speeding through landscapes and floating in in a white ground, has the effect of compressing time and space while expanding perspective, a dichotomy that would not be lost on the wandering Travis.

The first work I chose for the exhibition was Jan Cunningham’s Studio Chair, an empty platform in a monochromatic space, redolent with the ghosts of those who once rested there. It reminded me immediately of Walker Evans’ kitchen utensils hanging on an Alabama tenant farmer’s wall in 1936, a picture so full of the needs and touch of human life that I want to cry for all the absence and struggle it portrays. Cunningham’s chair proclaims its history but demands to be occupied. Whether it will ever be again seems in doubt. This absence of presence – the distinct perfume of emptiness seemed to me a theme throughout.

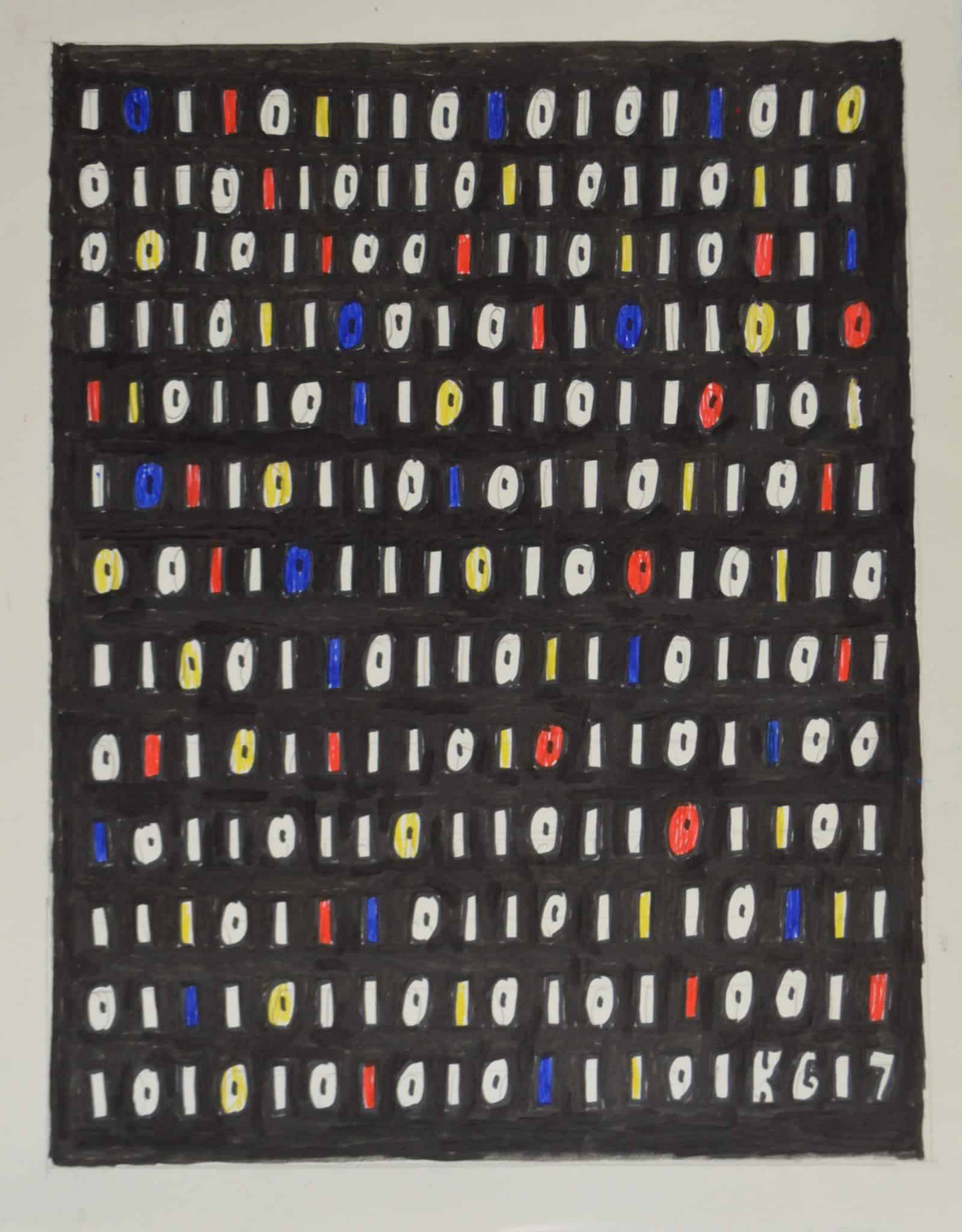

Absent of connections to people, life is reduced to the digital in Ken Grimes’ Untitled, a message waiting to be deciphered, a missive waiting to be heard. Memory is longing, for others once close by or places inhabited but now abandoned. Drawn like snapshots from a family album, mimicking the veracity of the photograph, Elizabeth Livingston and Beth Lovell create domestic scenes that are true but invented. Jungian in nature, they spout from some universal pool of experiences for many.

Victoria Crayhon’s movie theatres, with their existential marquee messages that would make any French New Wave auteur inwardly proud, ironically use one of the most common, universally shared community experiences of sitting in the dark with strangers to express individual secret fears and desires. Andrew Hogan’s footbridge in New Haven, a different architectural photograph, evokes a more lyrical existentialism, where the path is clear but the destination is unseen. Bathed in a warm morning light, there is hope and challenge.

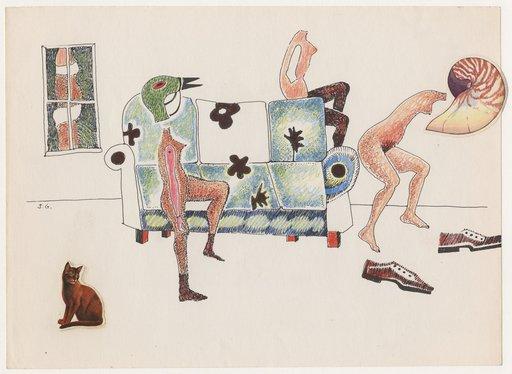

Joan Gardner’s drawn disembodied figures, David Coon’s strange Bathtub Mary, Deanna Lawson’s lone, isolated African American male senior, are all iterations of the figurative impulse, the heart of which is describing what it is like to observe the “other” – the self outside our selves. These works share a lonely existence, surely one of abandonment and quarantine. They beg us to look and to consider them as mirrors of our own selves.

Artists have to get their hands dirty. Manipulating materials, augmenting creations through adding and subtracting color, textures and mediums often define their jobs. Susan McCaslin’s sublime, rubbed and folded paper works are abstract architectural studies and therefore refer to home, or shelter. Selected for the exhibition, one drawing features the suggestion of a door but opening to where leaves the viewer guessing. Kathryn Frund’s Recovery works consist of a lathering of dark resin on the pages of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden decorated with star maps like the night sky, finding the Earth and the heavens on single plates from a great American story. Mercedes Teixido’s collages of food wrappers repurpose packaging in little decorative and intricately cut paper medallions. Simultaneously Surrealist and Pop, they are part Max Ernst, part Andy Warhol.

Exhibitions are stories too. In this case, it is a fiction, a narrative devised from the chance occurrences of what was seen and organized. Whatever conclusions are reached are the result of the journey that you, the viewer, takes as you leap off the cliff, into an unknown place. Somewhere, without language or streets.