Footnotes Guided Tour

Welcome to Footnotes and other embedded stories. We invite you to use the following audiovisual guide to navigate the paintings, installations, videos, woodcuts, and sculptures throughout the galleries of Artspace New Haven.

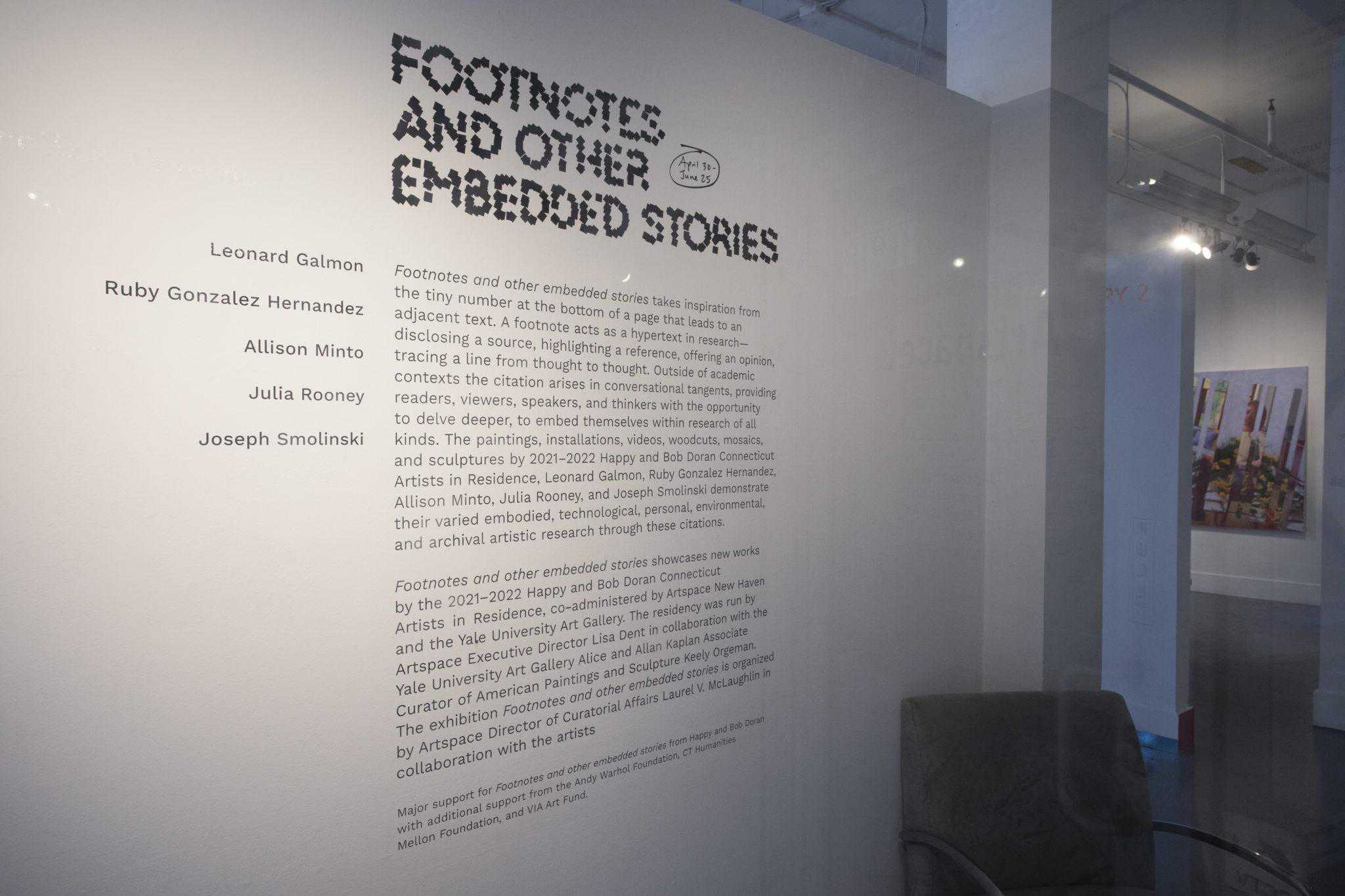

FOOTNOTES AND OTHER EMBEDDED STORIES April 30—June 25, 2022

Introduction

Footnotes and other embedded stories takes inspiration from the tiny number at the bottom of a page that leads to an adjacent text. A footnote acts as a hypertext in research—disclosing a source, highlighting a reference, offering an opinion, tracing a line from thought to thought. Outside of academic contexts the citation arises in conversational tangents, providing readers, viewers, speakers, and thinkers with the opportunity to delve deeper, to embed themselves within research of all kinds.

The paintings, installations, videos, woodcuts, mosaics, and sculptures by the 2021–2022 Happy and Bob Doran Connecticut Artists in Residence, Leonard Galmon, Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez, Allison Minto, Julia Rooney, and Joseph Smolinski demonstrate their varied embodied, technological, personal, environmental, and archival artistic research through these citations.

Footnotes showcases new works from the 2021–2022 Happy and Bob Doran Connecticut Artist-in-Residence Program, co-administered by Artspace New Haven and the Yale University Art Gallery. The residency was guided by Artspace Executive Director Lisa Dent in collaboration with the Yale University Art Gallery Alice and Allan Kaplan Associate Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture Keely Orgeman. The exhibition is organized by Artspace Director of Curatorial Affairs Laurel V. McLaughlin in collaboration with the artists.

The exhibition is accompanied by a free public programming series, including artist-led workshops, conversations, and public projects.

To learn more and RSVP, please visit artspacenewhaven.org/calendar

Major support for this exhibition from Happy and Bob Doran with additional support by the Yale University Art Gallery, Andy Warhol Foundation, CT Humanities, Mellon Foundation, and VIA Art Fund.

Notas al pie y otras historias incorporadas se inspira en el pequeño número en la parte inferior de una página que conduce a un texto adyacente. Una nota al pie actúa como un hipertexto en la investigación—revela una fuente, destaca una referencia, ofrece una opinión, traza una línea de pensamiento a pensamiento. Fuera de los contextos académicos, la cita surge en tangentes conversacionales, brindándoles a lectores, espectadores, oradores, y pensadores la oportunidad de profundizar, de integrarse en investigaciones de todo tipo. Las pinturas, instalaciones, videos, xilografías, mosaicos, y esculturas de Leonard Galmon, Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez, Allison Minto, Julia Rooney, y Joseph Smolinski, Artistas en Residencia Happy y Bob Doran de Connecticut para los años 2021–2022, demuestran sus variadas formas encarnadas de investigación tecnológicas, personales, artísticas, ambientales, y de archivo a través de estas citas.

Notas al pie y otras historias incorporadas presenta nuevas obras de la Residencia Happy Bob Doran de Connecticut para los años 2021–2022, coadministradas por Artspace New Haven y la Galería de arte de la Universidad de Yale. La residencia estuvo a cargo de la Directora Ejecutiva de Artspace, Lisa Dent, en colaboración con Keely Orgeman, Curadora Asociada de pintura y escultura americanas Alice y Allan Kaplan de la Galería de Arte de la Universidad de Yale. La exposición Notas al pie y otras historias incorporadas está organizada por la directora de asuntos curatoriales de Artspace, Laurel V. McLaughlin, en colaboración con los artistas.

Notas al pie y otras historias incorporadas se acompañan de una serie de programación pública gratuita, que incluye talleres dirigidos por artistas, conversaciones y proyectos públicos. Para obtener más información sobre la serie, visite el sitio web de Artspace, artspacenewhaven.org/calendar

Un gran apoyo para Notas al pie y otras historias incorporadas de Happy y Bob Doran con apoyo adicional de la Galería de arte de la Universidad de Yale, la Fundación Andy Warhol, CT Humanities, la Fundación Mellon, y VIA Art Fund.

Leonard Galmon

Leonard Galmon

In Uncle Fred (Breaking Ground #5), and Rocky (Posted #3), Leonard Galmon paints portraits of a family member and friend. Uncle Fred (Breaking Ground #5) captures an intimate moment of Uncle Fred as he relishes a cigarette before his day begins. Looking down at a phone, he looks away from the viewer, unconcerned by our gaze and absorbed in the everyday action. The release of the cigarette and casual looking are interspersed with the tentacular overgrowth of roots on an urban sidewalk that intersect with the subject’s dreadlocks. Two forms of grids with the sidewalk bricks and the vertical abstract lines hold tension between the curves of the portrait subject and the roots. It is as if the roots and the subject harbor multitudes that break expectations of neatness. Rather, the casual intensity of Uncle Fred, much like a meditation as the smoke gently creeps upwards. In Rocky (Posted #3), the subject lounges in a chair looking outward with a slight tilt to his head. The sinuous coherence of his figure contrasts with the regularity of the grid, revealing the A-frame of a house underneath. Behind Rocky, a plant leans over his shoulder, attempting to join the yellow flowers teeming across the architectural façade. What Rocky (Posted #3) and Uncle Fred (Breaking Ground #5) embody are portraits of Black men exceeding the limiting expectations that U.S. culture places upon people of color, and instead, imagine tender spaces of rest and reflection.

Breaking through a moody sky, the portrait subject and friend of the artist, Grace, stares out from the resting place of a couch. The vertical cuts of her interior space intersect with an outdoor view of a rooftop overflowing with golden flowers. Grace (Posted #2) is the most recent work in painter Leonard Galmon’s portrait series “Parallel Subversions.” In the series, Galmon compositionally undermines the rational and western structure of the grid as an objective device for truth-telling and reality within the tradition of painting through Black kinship, urban environments, affective color, and canvas treatment. Galmon paints Black friends, family, and acquaintances in positions of repose, contemplation, and imagining. Their figural complexity disrupts the rigid orderliness and abstraction of the grid structure that undergirds the composition. Grace looks away from viewers, unconcerned with our gaze. She looks out into what seems to be a space of her own creation. The overgrowth of flowers, perhaps signaling her teeming thoughts, undermines the urban plans designed for containment and reminds Galmon of New Orleans, his home, in which the destruction of the post-Katrina landscape offered new possibilities. The saturated colors allude to moods spent with the portrait subjects and shifting emotional states of the artist when working in his studio. And finally, the unprecious treatment of Galmon’s paintings, as they fray at the edges, demonstrate portraits lived with and beheld with care, not because they are hallowed art objects, but because the subjects are beloved. Black subjects, the urban spaces they call home, and their imaginaries exceed the grid.

En Tío Fred (Rompiendo esquemas #5) y Rocky (Publicado #3), Leonard Galmon pinta retratos de un familiar y un amigo. Tío Fred (Rompiendo esquemas #5) captura un momento íntimo del tío Fred mientras saborea un cigarrillo antes de que comience su día. Mirando un teléfono, aparta la mirada del espectador, indiferente a nuestra mirada y absorto en la acción cotidiana. La liberación del cigarrillo y la mirada casual se entremezclan con el crecimiento excesivo de raíces tentaculares en una acera urbana que se cruzan con las rastas del sujeto. Dos formas de cuadrículas con los ladrillos de la acera y la cuadrícula abstracta vertical mantienen la tensión entre las curvas del sujeto del retrato y las raíces. Es como si las raíces y el sujeto albergaran multitudes que rompen las expectativas de pulcritud. Más bien, la intensidad casual del tío Fred, muy parecida a una meditación mientras el humo lenta y suavemente se eleva. En Rocky (Publicado #3), el sujeto se recuesta en una silla mirando hacia afuera con una ligera inclinación de cabeza. La coherencia sinuosa de su figura contrasta con la regularidad de la cuadrícula, revelando el marco en A de una casa debajo. Detrás de Rocky, una planta se inclina sobre su hombro, intentando unirse a las flores amarillas que pululan por la fachada arquitectónica. Lo que encarnan Rocky (Publicado #3) y Tío Fred (Rompiendo esquemas #5) son retratos de hombres negros que superan las expectativas limitantes que la cultura estadounidense impone a las personas de color y, en cambio, imaginan los tiernos espacios de descanso y reflexión.

Atravesando un cielo melancólico, la retratada y amiga del artista, Gracia (Publicado #2), mira fijamente desde el lugar de descanso de un sofá. Los cortes verticales de su espacio interior se cruzan con una vista exterior de un techo rebosante de flores doradas. Gracia es la obra más reciente en laserie de retratos del pintor Leonard Galmon “Subversiones paralelas”. En la serie, Galmon socava compositivamente la estructura racional y occidental de la cuadrícula como un dispositivo objetivo para decir la verdad y la realidad dentro de la tradición de pintar a través del parentesco negro, los entornos urbanos, el color afectivo y el tratamiento del lienzo. Galmon pinta a amigos, familiares, y conocidos negros en posiciones de reposo, contemplación, e imaginación. Su complejidad figurativa interrumpe el orden rígido y la abstracción de la estructura de cuadrícula que sustenta la composición. Gracia aparta la mirada del público, despreocupada de nuestra mirada. Ella mira hacia lo que parece ser un espacio de su propia creación. El crecimiento excesivo de flores, tal vez indicando sus abundantes pensamientos en esta pintura, socava los planes urbanos diseñados para la contención y le recuerda a Galmon a Nueva Orleans, su hogar, en el que la destrucción del paisaje posterior a Katrina ofreció nuevas posibilidades. Los colores saturados aluden a los estados de ánimo pasados con los sujetos del retrato y los cambiantes estados emocionales del artista cuando trabaja en su estudio. Y, finalmente, el tratamiento poco precioso de las pinturas de Galmon, al deshilacharse en los bordes, demuestran retratos vividos y contemplados con cuidado, no porque sean objetos de arte sagrados, sino porque los sujetos son amados. Los sujetos negros, los espacios urbanos que llaman hogar, y sus imaginarios superan la cuadrícula.

Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez

Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez

With her great aunt and mother holding up her sweet-sixteen dress from storage, artist Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez recalls the evening she wore it and her simultaneous decision to leave Pentecostalism in this first work from her series “Subseven.” She arrests this moment in time first through its photographic source from her cellphone and then the transformation of the cellphone digital coding through the layered coding of Photoshop, VCarve, and LinuxCNC to render the image. Via a CNC router on birchwood panel at a bodily-sized scale, Gonzalez Hernandez then prints the panel on absorbent Masa paper. The various layers of the print register the ink differently, causing the image to be stark in certain spaces and spare in others. As the artist explains, “these prints themselves look more disintegrated the closer you get while becoming clearer the farther away, and that speaks to the point of view you can maintain, while being engulfed in extremism.” The processes she uses specifically “specifically “follow the same painful dialog to physically imitate what it took to get here, to a completely different life. I’m using references from this past to acknowledge what I’ve given myself, completely separate from assigned religious, immigrant, and familial structures,” as the artist says, “and reconstruct a material language of self-determination.”

Freedom Had A Bitter Taste, Atonement, and Waiting For A Sealed Fate all depict reflective surfaces and spaces, whether through mirrors placed in New Haven’s East Rock woods or the empty and exposed outdoor room of a mulch dumping site. These opportunities for reflection offer meditation for artist Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez to consider “someone I once was, in the language she understood.” The wild sites of forests and earth piles from her job working for a mulching company represented in the works relay a sense of freedom in the “outside world,” which contrasts starkly to the strictures of her past in an intentional community, also called a cult. Gonzalez Hernandez translates these meditative processes through materiality in her woodcut print series “Subseven” on Masa. The title “Subseven” refers to a submission to God. But these photographic prints remove themselves from the obligation to submit and instead wield agency. Using processes of coding, CNC routing, and printing that last as long as eleven hours, Gonzalez Hernandez inscribes layers of her experience and introspection on the surfaces of the wood. Repeating this process over and again in each of the works in the series, the artist carves out space for the listening to and reimagination of herself.

Con su tía abuela y su madre sosteniendo su vestido de quinceañera guardado, la artista Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez recuerda la noche en que lo usó y su decisión simultánea de dejar el pentecostalismo en esta primera obra de su serie “Subsiete.” Ella captura este momento en el tiempo, primero a través de su fuente fotográfica desde su teléfono celular, y luego la transformación de la codificación digital del teléfono celular a través de la codificación en capas de Photoshop, VCarve, y LinuxCNC para renderizar la imagen. A través de un enrutador CNC en un panel de madera de abedul a escala del tamaño del cuerpo, Gonzalez Hernandez luego imprime el panel en papel absorbente Masa. Las diversas capas de la impresión registran la tinta de manera diferente, lo que hace que la imagen sea marcada en ciertos espacios y sobria en otros. Como explica el artista, “estas impresiones en sí mismas se ven más desintegradas cuanto más te acercas, mientras que se vuelven más claras cuanto más te alejas, y eso habla del punto de vista que puedes mantener, mientras estás sumergido en el extremismo”. Los procesos que usa “específicamente siguen el mismo diálogo doloroso para imitar físicamente lo que tomó para llegar aquí, a una vida completamente diferente. Estoy usando referencias de este pasado para reconocer lo que me he dado a mí misma, completamente separado de las estructuras religiosas, inmigrantes, y familiares asignadas”, como dice la artista, y reconstruir un lenguaje material de autodeterminación.

La libertad tuvo un sabor amargo, Expiación, y Esperando un destino sellado representan superficies y espacios reflectantes, ya sea a través de espejos colocados en los bosques de East Rock en New Haven o en la habitación exterior vacía y expuesta de un vertedero de mantillo. Estas oportunidades de reflexión ofrecen meditación para que la artista Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez considere “alguien que alguna vez fui, en el idioma que ella entendía”. Los sitios salvajes de bosques y montones de tierra de su trabajo para una empresa de mulching representados en las obras transmiten una sensación de libertad en el “mundo exterior”, que contrasta marcadamente con las restricciones de su pasado en una comunidad intencional, también llamada culto. Gonzalez Hernandez traduce estos procesos meditativos a través de la materialidad en su serie de xilografías “Subseven” sobre Masa. El título “Subsiete” se refiere a una sumisión a Dios. Pero estas fotografías se eliminan a sí mismas de la obligación de someterse y, en cambio, ejercen agencia. Usando procesos de codificación, enrutamiento CNC, e impresión que dura hasta once horas, Gonzalez Hernandez inscribe capas de su experiencia e introspección sobre las superficies de la madera. Repitiendo este proceso una y otra vez en cada una de las obras de la serie, la artista crea un espacio para la escucha y la reimaginación de sí misma.

Allison Minto

Allison Minto

In the experimental video Structures of Identity, Allison Minto presents a past, present, and futural archive. Composed from familial, found, and new footage, the video traces a non-linear speculating upon conceptions of Blackness through multiple iterations of unrealized Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), both in Minto’s personal life and in New Haven. HBCUs offered higher education to African Americans in the United States prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ensuring that Black excellence flourished. Minto recalls the Black self-formation articulated by alumni of HBCUs, largely considered hallowed institutions, especially in communities from the South. Her footage of Black traditions of color guard and the sound of marching bands from New Haven’s James Hillhouse High School rehearsals, and found footage, photos, and her sister Diana’s recreated color guard uniform by designer Dwayne Moore, demonstrate observation from the periphery as she never attended an HBCU. Such footage contrasts with that of an intersection of New Haven’s I-95 and I-91 highways that Minto renders elegiac. The site is what would have been the United States’ first HBCU, proposed in 1831 at the First Annual Convention of the Free People of Color convened in Philadelphia. That same year, white property owners put pressure on the city of New Haven, which eventually voted against the college’s existence. And finally, ending meditative shots track speculative structures of identity she could have known through the intellectual and communal kinships forged at an HBCU.

En el video experimental Estructuras de identidad, Allison Minto presenta un archivo pasado, presente y futuro. Compuesto a partir de imágenes familiares, encontradas y nuevas, el video rastrea una especulación no lineal sobre las concepciones de la negritud a través de múltiples iteraciones de universidades e instituciones históricamente negras no realizadas (HBCU), tanto en la vida personal de Minto como en New Haven. Las HBCU (Universidades históricamente negras) ofrecían educación superior a los afroamericanos en los Estados Unidos antes de la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1964, asegurando que floreciera la excelencia negra. Minto recuerda la autoformación negra articulada por ex alumnos de las HBCU, en gran parte consideradas instituciones sagradas, especialmente en comunidades del sur. Su material de archivo de las tradiciones negras de los abanderados y el sonido de las bandas de música de los ensayos de New Haven James Hillhouse High School, y las imágenes encontradas, fotos, y el uniforme de abanderada de su hermana Diana, recreado por el diseñador Dwayne Moore, demuestran la observación desde la periferia ya que ella nunca asistió a una HBCU. Ese metraje contrasta con el de una intersección de la I-95 y la I-91 de New Haven que Minto convierte en elegíaco. El sitio es lo que habría sido la primera HBCU de los Estados Unidos, propuesta en 1831 en la Primera Convención Anual de la Gente Libre de Color convocada en Filadelfia. Ese mismo año, los propietarios blancos presionaron a la ciudad de New Haven, que finalmente votó en contra de la existencia de la universidad. Y, finalmente, las tomas meditativas finales rastrean estructuras especulativas de identidad que podría haber conocido a través de los parentescos intelectuales y comunales forjados en una HBCU.

Julia Rooney

Julia Rooney

Greenscreen is an installation consisting of a freestanding six-by-six-foot painting upheld by found cast-iron bench legs, which casts a shadow on two-by-two-inch paintings mounted on a nearby wall. The large canvas, painted with chroma key green, references the greenscreen, a cinematic tool in which objects and people have the ability to enter digital realms other than the present through the camera’s non-registration of that color. The smaller painted canvases featuring a naturalistic range of greens cite historic landscape paintings from the Yale University Art Gallery’s collection and, by extension, the traditional notion that paintings offer windows to the world optically. Repainting only two-by-two-inch excerpts of the original paintings, Rooney nods to the scale and quality with which we now view art on our phones through apps like Instagram, inviting us to consider: What and how are we seeing through these digital devices?

On the opposite side of the large canvas and color spectrum, pink magenta registers the varied skin tones of users. The cast-iron legs further anthropomorphize the painting, elevating it to the height of a seat and returning it back to an analog era. The square cut-outs and the mirrored side panels animate viewers’ encounters with the work—allowing them to literally look through the painting, or at the spotlights on the miniature paintings which are hung in corresponding arrangement, or even at their own reflections on its sides. Instead of occupying the wall as static works for contemplation, Rooney’s installation recasts painting as a persistent technology that acts upon the faculties of sight and imagination.

Julia Rooney’s hand-cast paper scrolls collectively hang from Artspace’s ceiling in an immersive site-specific installation, Scrollscape. Composed from blue, black, white, and gray pigmented cotton and denim pulp, viewers can see the installation from the sidewalk with the Orange-Street-facing window, which mediates their experiences at a distance, or from within the gallery, as walking bodies generate the spinning circulation of each scroll. The empty walls too are activated by the scrolls’ shadows, which change with the weather and viewers’ movements. This toggling between “front” and “back”—activated by viewers’ behaviors—evokes a feedback loop in which one data set produces another data set and is, in turn, reproduced over and over. Body-scaled and mobile, the scrolls are suggestive of personas—different from yet related to a person who has created a version of themselves online. While apps like Instagram or Facebook often privilege the optical experience of looking at images, Rooney’s installation asks a radical question: what does the embodiment of this experience feel like? How does the interaction of real persons with online personas affect the behavior of both?

Alongside the scrolls, Rooney’s cubed Text Box and Hearing… newsprint sculptures function as mobile seats and accessible reading material that reveal the juridical and cultural architectures conditioning these contemporary digital ways of looking and behaving. Rooney read and indexed the U.S. Senate hearings with Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg, noting keywords in the online public text, meticulously transcribing them by hand, organizing them alphabetically, and reproducing them for peripheral or direct use in the installation. Rooney’s environment asks viewers to reconsider the mediated ways in which they register embodiment and vision. Whether immersed in the space or viewing it from a distance, how are we all implicated in this cycle?

Pantalla verde es una instalación que consiste en una pintura independiente de seis por seis pies sostenida por patas de banco de hierro fundido encontradas, que proyecta una sombra sobre pinturas de dos por dos pulg. montadas en una pared cercana. El gran lienzo, pintado con clave de croma verde, hace referencia a la pantalla verde, una herramienta cinematográfica en la que los objetos y las personas tienen la capacidad de ingresar a espacios digitales distintos al presente a través del no registro de ese color por parte de la cámara. Los lienzos pintados más pequeños que presentan una gama naturalista de verdes citan pinturas de paisajes históricos de la colección de la Galería de Arte de la Universidad de Yale y, por extensión, la noción tradicional de que las pinturas ofrecen ventanas al mundo ópticamente. Repintando solo extractos de dos por dos pulg. de las pinturas originales, Rooney asiente a la escala y la calidad con la que ahora vemos el arte en nuestros teléfonos a través de aplicaciones como Instagram, invitándonos a considerar: ¿Qué y cómo estamos viendo a través de estos dispositivos digitales?

En el lado opuesto del gran lienzo y espectro de colores, el rosa magenta registra los variados tonos de piel de los usuarios. Las patas de hierro fundido antropomorfizan aún más la pintura, elevándola a la altura de un asiento y devolviéndola a una era analógica. Los recortes cuadrados y los paneles laterales espejados animan los encuentros de los espectadores con la obra—permitiéndoles mirar literalmente a través de la pintura, o a los focos de las pinturas en miniatura que están colgadas en la disposición correspondiente, o incluso a sus propios reflejos en su lados. En lugar de ocupar la pared como obras estáticas para la contemplación, la instalación de Rooney reformula la pintura como una tecnología persistente que actúa sobre las facultades de la vista y la imaginación.

Los rollos de papel fundidos a mano de Julia Rooney cuelgan colectivamente del techo de Artspace en una instalación inmersiva específica del sitio, Paisaje de desplaces. Compuesto de pulpa de mezclilla y algodón pigmentada en azul, negro, blanco, y gris, el público puede ver la instalación desde la acera con la ventana que da a la Calle Orange, que media sus experiencias a distancia, o desde dentro de la galería, mientras los cuerpos ambulantes generan la circulación giratoria de cada desplace. Las paredes vacías también se activan con las sombras de los desplaces, que cambian con el clima y los movimientos del público. Esta alternancia entre “anverso” y “reverso” — activada por el comportamiento del público—evoca un ciclo de retroalimentación en el que un conjunto de datos produce otro conjunto de datos y, a su vez, se reproduce una y otra vez. A escala corporal y móviles, los desplaces sugieren imágenes personales—diferentes pero relacionadas con una persona que ha creado una versión de sí misma en línea. Si bien las aplicaciones como Instagram o Facebook a menudo privilegian la experiencia óptica de mirar imágenes, la instalación de Rooney plantea una pregunta radical: ¿cómo se siente la encarnación de esta experiencia? ¿Cómo afecta la interacción de personas reales con imágenes personales en línea al comportamiento de ambos?

Junto a los desplaces, las esculturas de papel de periódico Cuadro de texto y Audiencia… de Rooney funcionan como asientos móviles y material de lectura accesible que revelan las arquitecturas jurídicas y culturales que condicionan estas formas digitales contemporáneas de mirar y comportarse. Rooney leyó e indexó las audiencias del Senado de EE. UU. con el director ejecutivo de Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, anotó palabras clave en el texto público en línea, las transcribió meticulosamente a mano, las organizó alfabéticamente, y las reprodujo para uso periférico o directo en la instalación. El entorno de Rooney le pide al público que reconsidere las formas mediadas en las que registran la personificación y la visión. Ya sea sumergidos en el espacio o viéndolo desde la distancia, ¿cómo estamos todos implicados en este ciclo?

Joseph Smolinski

Joseph Smolinski

Mourning Sun and Hurricane are mosaic works composed from found sea coal on the Connecticut coast-lines. Artist Joseph Smolinski gleans the coal on meditative walks or family trips, recalling that the material was likely mined in the southern U.S. and shipped to the historic and global port of New Haven. The coal now mixes with the sifting sands of northern shores, often unnoticed by human eyes. Arranged intentionally once more in Mourning Sun (left) and Hurricane (right) to evoke a sunset and tropical storm, respectively, Smolinski highlights its texture—whether soft and brittle, or hard and steely—denoting the age of hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen under pressure. This texture determines its reflective quality, which the artist positions to determine spatial depth and light. In each composition depicting natural phenomena of weather, the depth of time that it takes to naturally produce coal clashes with its short-sighted extractive use as a fuel source that contributes to radical weather. Smolinski implicates the temporality and texture of coal within the climate system he extensively researches while also rendering such qualities aesthetically as they catch the light.

In Climate Repository Joseph Smolinski references the history of the cabinet of curiosity—or, as it was referred to in 16th-century Europe, the “Wunderkammer,” literally meaning “wonder chamber” in German—but distinctly subverts its exclusive modes of sight, material, and display. Historically, these pieces of furniture owned by the elite displayed exoticized objects collected on grand expeditions—often to colonized territories in which natural resource extraction took place—for display in private homes. Rather than replicating the curated containers, Smolinski renders the design of the structure open as shelving instead of closed, gesturing towards open access and democratic viewership. The contemporary curio-cabinet is sourced from found and public materials, specifically a salvaged tree that fell on the New Haven Green, rather than harvesting rare woods often seen in the early modern period. The objects seen throughout Climate Repository, such as 3D-scanned and 3D-printed melting snow piles, a broken rear-view mirror left on the road, and laser-etched acrylic sheets bearing images of breaking sea ice, reference Smolinski’s process of material and object collection and considering the levels of human intervention upon the planet that the objects emblematize. As this curio-cabinet demonstrates, interactions with so-called nature can be small or immense. Throughout the exhibition, the artist will add objects, rearrange them, and augment the collection. Smolinski invites audiences to interact with the objects carefully, acknowledging their places within the climate system.

The artist and Artspace New Haven welcome viewers to submit plans for a maximum 4 x 4 x 4 in.-object to this ongoing work. To submit your object to Joseph Smolinski’s Climate Repository, send laurel@artspacenh.org an email with a photograph of the object, a 2-3 sentence description of the object, and 1-sentence explanation of why you think it would fit in this work.

These works were made possible in part by the Connecticut Sea Grant.

Sol de luto y Huracán son obras de mosaico compuestas de carbón marino (carbón mineral desechado al océano/mar) encontrado en las costas de Connecticut. El artista Joseph Smolinski recoge el carbón en caminatas meditativas o viajes familiares, recordando que el material probablemente se extrajo en el sur de los EE. UU. y se envió al puerto histórico y global de New Haven. El carbón ahora se mezcla con las arenas cribadas de las costas del norte, a menudo desapercibidas por los ojos humanos. Ordenados intencionalmente una vez más en Sol de luto (izquierdo) y Huracán (derecho) para evocar una puesta de sol y una tormenta tropical, respectivamente, Smolinski resalta su textura—ya sea blanda y quebradiza, o dura y acerada—que denota la edad del hidrógeno, azufre, oxígeno, y nitrógeno bajo presión. Esta textura determina su cualidad reflectante, que el artista posiciona para determinar la profundidad y luz del espacio. En cada composición que representa los fenómenos naturales del clima, la profundidad del tiempo que lleva producir carbón de forma natural choca con su uso extractivo miope como fuente de combustible que contribuye al clima radical. Smolinski implica la temporalidad y la textura del carbón dentro del sistema climático que investiga exhaustivamente al mismo tiempo que representa estéticamente esas cualidades a medida que captan la luz.

En Almacén climático, Joseph Smolinski hace referencia a la historia del gabinete de curiosidades—o, como se le conocía en la Europa del siglo XVI, el “Wunderkammer”, que literalmente significa “cámara de las maravillas” en alemán—pero claramente subvierte sus modos exclusivos de visión, material, y exhibición. Históricamente, estos muebles propiedad de la élite exhibieron objetos exóticos recolectados en grandes expediciones—a menudo a territorios colonizados en los que se llevó a cabo la extracción de recursos naturales—para exhibirlos en casas particulares. En lugar de replicar los contenedores curados, Smolinski presenta el diseño de la estructura abierto como estantería en lugar de cerrado, apuntando hacia el acceso abierto y un público democrático. El gabinete de curiosidades contemporáneo proviene de materiales encontrados y públicos, específicamente un árbol rescatado que cayó en el parque New Haven Green, en lugar de cosechar maderas raras que se ven a menudo en el período moderno temprano. Los objetos que se ven en el Repositorio Climático, como montones de nieve derretida escaneados e impresos en 3D, un espejo retrovisor roto dejado en la carretera y láminas acrílicas grabadas con láser que muestran imágenes de hielo marino rompiéndose, hacen referencia al proceso de Smolinski de material y colección de objetos y considerando los niveles de intervención humana sobre el planeta que los objetos simbolizan. Como demuestra este gabinete de curiosidades, esta interacción con la llamada naturaleza puede ser pequeña o inmensa. A lo largo de la exposición, el artista agregará objetos, los reorganizará, y aumentará la colección. Smolinski invita al público a interactuar con los objetos cuidadosamente, reconociendo sus lugares dentro del sistema climático.

El artista y Artspace New Haven invitan al público a enviar planes para un objeto de un máximo de 4 x 4 x 4 pulg. para esta obra en curso. Para enviar su objeto al Almacén climático de Joseph Smolinski, envíe un correo electrónico a laurel@artspacenh.org con una fotografía del objeto, una descripción de 2–3 oraciones del objeto, y una explicación de 1 oración de por qué cree que encajaría en esta obra.

Estas obras fueron posibles en parte gracias a Connecticut Sea Grant.