Fifteen Years of CWOS: Looking forward, looking back

By Hank Hoffman

Artist Chris Mir in his Erector Square studio at City-Wide Open Studios. (2004, photo by Leslie Kuo)

Creating Community

This fall’s City-Wide Open Studios, extending through the first three weekends of October, marks the event’s 16th anniversary. Mir is but one of hundreds of local artists — lifelong dedicated professionals and enthusiastic amateurs alike — who are grateful for the exposure gained by participation in CWOS. Helen Kauder recalls artists gathering on a loading dock at Erector Square early Sunday morning in 1998, the first year of City-Wide Open Studios. Before they opened their studio doors for the day, they assembled for a group photo shoot.

“What we saw was people shaking hands, meeting each other for the first time, people who had worked at Erector Square for many years,” Kauder says in an interview, reflecting on CWOS’ 16th anniversary. “That sense of networking and community meant a lot to us.”

“Community” is the word that comes up most often in discussions with artists about City-Wide Open Studios. CWOS became a platform through which the extent and depth of New Haven’s visual arts community could be showcased and also a vehicle for artists — who most often work in isolation in their studios — to connect with other artists.

Exploring Alternatives

But even from its inception, the event was about more than just opening studios to curious visitors. A small “d” democratic inclusiveness is a hallmark of the event. Consider yourself an artist? Then you are welcomed to participate. The temporary galleries known as the “alternative space(s)” are signature attractions. Magnets for artists without studios to open, the alternative spaces also serve as laboratories for experimentation and a way to revitalize neglected urban spaces. Art commissioned in conjunction with the event — in storefront windows and in the vacant tract at Chapel and Orange streets known as The Lot, among other locations — raises the public profile of the event and visual art in general. Marianne Bernstein, co-founder of the event with Kauder and artist Linn Meyers, says that CWOS is more of a festival, “Open Studios-plus.”

Certainly, there had been other organizing efforts by artists in New Haven in the previous decade or two, including Artists Working in New Haven and Papier Mache Video Institute. But by the late 1990’s, those efforts were faltering or were defunct. Important galleries in New Haven had recently closed. The art economy was in a slump. Artspace, headquartered on Audubon Street, faced crises both financial and mission-related. Bernstein was on the board of Artspace at the time and head of its visual arts committee. Because artists couldn’t afford space anymore, Bernstein suggested to Artspace’s board that the organization “think of the city as an ‘artspsace,’ not necessarily a physical building.” Under the rubric of “untitled (space),” she was exploring the concept of creating temporary galleries in vacant storefronts. The idea for such alternative spaces arose from Bernstein’s desire — other art activists in other cities were exploring the same concepts, she recalls — to conjure “new ways to get the public to interact with art and

These 18×18″ grid squares have become a CWOS trademark, showcasing a representative work from each artist at the main exhibition. (2004, lk)

Bernstein had forged a friendship with painter Linn Meyers. Meyers, who had participated in an Open Studios event in San Francisco, suggested trying it in New Haven. She also conceived the grid format for the main exhibition, allotting each artist 18 square inches in which to show a representative work. Kauder completed the trio, bringing not just organizing and fundraising savvy but also an open-minded appreciation of contemporary visual arts and its importance to a community. She had visited the Bay Area as a tourist during Open Studios and “seen the city in a way open up to me and reveal its magic.” Kauder credits initial collaborators Bernstein and Meyers for the event’s inclusive spirit. “There was a feeling that that was something missing in the art world — this idea of the direct, unmediated presentation of art,” she says. “This could be an opportunity where the artist chooses the piece in the show, how they’re going to participate, whether to show old or new work, be in their own studio or in some other space, whether they’re going to be creating something site-specific.”

Other artists turn the Alt Space into temporary studios, letting visitors experience their working process. (CWOS 2004, Barnard & Beecher Schools, lk)

The Alternative Space makes it possible for artists to create site-specific installations like this mural.

The alternative space experiments were incorporated into the event as a solution to the problem of including artists who either didn’t have a studio to open or — in the case of at least one artist whose studio was in her home garage — feared doing so at a time when violent crime was plaguing New Haven. Kauder was then working at Yale, which was gearing up for a celebration of the university’s tercentennial. Eager to project a welcoming face and overcome its reputation for having a closed, gated campus, the school facilitated the availability of lobbies and vacant storefronts as temporary, pop-up exhibition sites. The alternative sites’ combination of raw space and liberated experimentation was an immediate hit among both artists and visitors. “New Haven needed to be encouraging creativity without judgment,” says Bernstein. The word “open,” in Bernstein’s opinion, was a key element in City-Wide Open Studios. “I thought art should be taken seriously [but] thought there was room for all kind of art-making. What New Haven needed was not more serious art-making but a more playful attitude toward artists and for artists to be encouraged to do whatever they wanted to do, to keep it as free and open as possible.”

“Initially, some more serious artists were a little skeptical because I was saying basically anyone who wants to be an artist can be an artist. ‘Well, what about the good artists? Are you going to mix [them in with] really awful artists?'” Bernstein remembers. “In their minds it was sort of like blasphemy. Nobody would be taken seriously.”

Reservations notwithstanding, the inclusive ethic also served the important goal of broadening the audience. It enabled event organizers to find new artists, including artists outside the mainstream. “We could expand the audience because the audience for the event is so tied to who’s participating,” says Kauder.

Similarly, the incorporation over the years of public art projects and experiments like one year’s mobile exhibition site for zines in an Airstream RV are “carefully thought out strategies to expand the platform of the event, to create some variety for audiences from year to year,” according to Kauder. While the alternative spaces became part of the event package for reasons of inclusiveness and experimentation, it turned out they served another purpose, too: making forlorn real estate more attractive to future buyers or tenants. In CWOS’ second year, real estate developer David Goldblum offered space in his recently acquired 39 Church Street building in the hope that some artists would rent studios there after the event. It worked. Kauder says that it was the first time event organizers “realized we could be a partner in redevelopment.”

“We have been very explicit about it ever since when we reach out to landlords and developers. This year is no different. We’re going to be in the New Haven Register building, which is on the market,” says Kauder. “Other spaces [used as alternative spaces] have gone on to find tenants, new uses or buyers. On some level, we can take credit for the evolution of what’s happened to those spaces.”

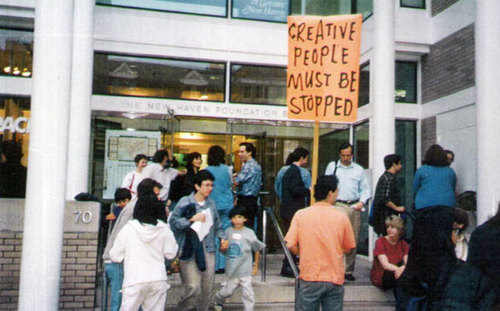

From the start, an overwhelming response

The organizers felt that first CWOS would be successful “if 75 artists stepped forward and opened their studios,” recalls Kauder. But, Marianne Bernstein reveals, the event almost died aborning.

According to Bernstein, Kauder and Meyers were skeptical about who was going to sign up. And sure enough, the deadline came and went with hardly any response.

“I remember Helen and Linn said, ‘Oh my God, this is not going to happen!’ I said, ‘No, are you kidding me? You have to use reverse psychology. What we’re going to say — we don’t need to lie — but we’re going to say, ‘The response is so overwhelming that we have decided to extend the deadline.’ Overwhelming for us meant overwhelmingly awful but I used the word ‘overwhelming,'” recalls Bernstein. “All of a sudden it was like Christmas — applications in bushels started coming through. That’s when we knew we were onto something. But if we had given up after the first deadline, there would be no Open Studios.”

In fact, some 200 artists participated that first year. City-Wide Open Studios estimated about 2,000 visitors checked out artists’ studios and the alternative spaces during the inaugural weekend.

“Opening night was so exciting. There was so much energy in the room and everybody was so happy and excited,” says Marianne Bernstein. “It took on a life of its own. The first weekend I remember thinking, ‘Look at this!’ It was something everybody was waiting for — the right event at the right moment in time.”

In the years since, the numbers of participating artists have fluctuated between 200 and 500, depending on the availability of expansive alternative spaces and the group participation of local university art departments. The event has attracted upwards of 10,000 visitors in some years with sales attributable to CWOS in a given year totaling as much as $54,000. (That is pre-recession, unsurprisingly.)

Artist Johanna Bresnick, who was artist coordinator at Artspace for about six years, knows firsthand what a massive undertaking City-Wide Open Studios is, especially the alternative space aspect of it. “In the summer I was working about 4-6 hours a day. By October, you’re working 16 hours a day straight with no days off. There are so many moving parts that have to be coordinated. A lot of it is behind the scenes. From inside, having been one of those people trying to keep it together, it’s so over the top in the amount of human energy it takes to get it going and it’s so dependent on volunteers.” The event is in a constant state of evolutionary flux as organizers struggle to keep it fresh and respond to feedback from participating artists. For this 15th Crystal Anniversary, Artspace is experimenting for the first time with suggesting a theme for interested artists — appropriately, “crystal” in its plethora of physical, cultural and symbolic manifestations. Participation is optional. But those artists who crystallize works around the theme will be rewarded with special signage in the studios, guided studio visits and notice in a media campaign.

Connecting, motivating, inspiring artists

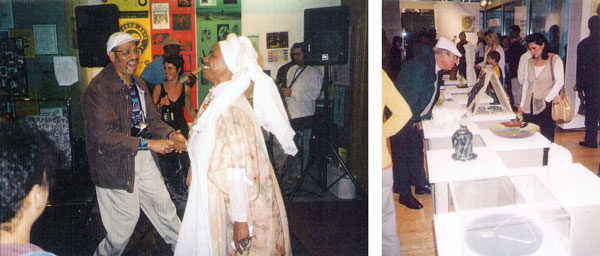

Left: artists Yolanda Petrocelli and Joan Fitzsimmons in dialogue at CWOS opening night. Right: artists gather to plan CWOS — and get to know one another.

For the artists who have participated in City-Wide Open Studios, the event has offered a multiplicity of rewards and opportunities. Sales. Exposure. Networking. An annual unjuried exhibition opportunity that serves as motivator and deadline. The social aspect is also important. New to town? City-Wide Open Studios is a great way to integrate into the local visual arts community. The event affords an opportunity not just to have one’s own work seen but also to visit the studios of other artists, event schedule permitting. The alternative spaces present an opportunity for experimentation and taking risks, whether on one’s own or in collaboration. CWOS fosters dialogue — among artists and visitors, artists and other artists and also — for artists creating site-specific installations — between artists and their environment.

Artists are among CWOS’s most enthusiastic visitors. Here, artist Chris Engstrom contemplates a collage in Matthew Feiner’s studio (2004, lk)

“I think it made me so much more aware of how many artists live and work in New Haven and gave us something of a forum for coming together and interacting with each other,” declares mixed media and installation artist Rita Valley. Where bumping into other artists at openings can have a competitive aspect, “Open Studios is very democratic in the best sense. We’re all given space and all allowed to do what we want to do to take chances or put our best foot forward.”

“More than anything else, it brought me into the New Haven art world,” says photographer Kevin Van Aelst, who participated for the first time shortly after moving to the area. It also boosted his professional confidence. “My first few years doing it, I showed lots of smaller prints that I made especially for the event to sell cheap. It was a tremendous boost coming out of graduate school and then getting some money from art.” Van Aelst met his wife Kim, also an artist, on a CWOS bike tour. This year, they will be opening their studio in their new home in Hamden for the first time. Loretta Staples moved to New Haven from New York City after happening upon promotion for the event while visiting a friend in town. “I got a flyer and was surprised to see there was both such an event and a large community of artists,” Staples says.

“For myself and a lot of artists working in New Haven, October becomes a built-in deadline for making work,” says Johanna Bresnick. Her participation in Open Studios has ranged from opening the doors of her home and former Erector Square studios to showing and creating site-specific installations in alternative spaces to working behind the scenes for Artspace as artist coordinator. “Even if you do have other exhibition obligations, there is the feeling that October is a time when something should be wrapped up and made show-ready.”

Photographer Kevin Van Aelst concurs. “You’ve got to get a handful of new pieces ready or, if things are in the works, what better occasion to have them finished than when a whole crowd of people are coming into your space?”

Rita Valley looks on City-Wide Open Studios as “my kind of laboratory for experimentation.” Working in alternative spaces, Valley has created large, provocative and fun site-specific installations such as “Wet Van,” a mobile art project that combined oil and water — and lots of plastic tape — to ingenious effect, and “Be Reborn Through Art,” a big birth canal with a large vagina for an exit. For the latter work, shown at the Science Park alternative site in 2003, visitors could walk through the installation and have their picture taken “enjoying a kind of metamorphosis into a new creative being,” according to Valley. CWOS is an ideal venue for participatory work, Valley says, “because it’s not in a gallery where it’s regimented. City-Wide Open Studios is almost a free-for-all and lets me be as wild and wacky as I want to be.”

Different audiences, different art, different encounters

Loretta Staples has invited visitors to her home studio in Daggett Square. She was inspired to move to New Haven by City-Wide Open Studios. (2004, lk)

True to the original intention of CWOS’ founders, artists find that their interactions with visitors tend to be different than what they might experience in a gallery show. Part of this is attributable to the audience. Loretta Staples, who participated in CWOS for three years in her Daggett Street home and studio, says, “The visitors who came were very wide-ranging, from very seasoned, sophisticated artists and collectors to people just from New Haven who wanted a fun day with their family and to see what’s going on.”

Valley contends that CWOS attracts many visitors for the festival atmosphere. “Because Open Studios tends to be so rough and tumble, you get a lot of people, like kids from the neighborhoods who might not go to a museum or gallery, coming in and going ‘What are you doing?’ That’s nice. It opens up all kinds of different audiences,” says Valley. “I would much rather have someone say, ‘What are you doing and why is that art?’ than ‘I like your work’ and kind of know what they’re looking at. It’s a good way to educate people.”

Valley’s comment gets to the heart of one of the strengths of CWOS — the way the combination of inclusiveness and informality allows challenging work to get a fair hearing. In a gallery setting a visitor might feel too intimidated to question a difficult work of art. But whether in a studio context or a sprawling alternative space — where, as Johanna Bresnick notes, “You have people coming with flower paintings next to somebody’s shredded furniture and glass stuck together with red paint all over it” — informality invites curiosity. In 2002, installation artist Ezra Parzybok described CWOS as “a welcoming format for the novice audience,” a way to bridge the gap between the familiar and the (seemingly) inaccessible.

Matthew Feiner, owner of The Devil’s Gear bicycle shop, has been both a participating artist and a leader of City-Wide Open Studios bike tours. The tours are organized to expose riders to varied art experiences, not just the most popular or well-known artists. Artists outside the mainstream get exposure.

“I love seeing people’s reactions going into someplace a little gritty and rough around the edges. People come out of those experiences having learned something about themselves or something about their boundaries, whether its physical or artistic boundaries,” says Feiner.

A couple of years ago the tour visited Wilfred Rembert’s studio in Newhallville. Rembert, who is African-American, carves and paints pieces of leather with scenes remembered from his youth in the South. When the bicyclists realized they were headed to Newhallville, a low-income neighborhood with a reputation for high crime rates, Feiner says many were quite uncomfortable. “But afterwards, [with] the rich stories that man told and the scenes he portrayed in his artwork, people weren’t there anymore,” Feiner recalls. “They were somewhere great, and they realized everywhere they went, they were somewhere great.”

Johanna Bresnick says that studio visitors “feel much more comfortable asking you details about how you make things” in ways they don’t at a gallery opening. “In an artist’s studio — since [artists] are kind of already opening up an extension of their psychic space — you’re already invited in a little bit. It’s an entrée into the conversation.”

A work in progress in Nathan Lewis’s studio, with dozens of reference photos taped below it (2004, lk).

A work in progress in Nathan Lewis’s studio, with dozens of reference photos taped below it (2004, lk).

Barbara Harder demonstrates the printmaking process in her studio (2004, lk).

Studio visits can demystify the process of making art or, as Bresnick quips, “uncover the magician’s tricks.” The source material for her work is there, “not just books but images of things that I’m thinking about, little scraps of pieces I’ve been playing with… a lot of times you’re looking at pieces of ideas, which I think is interesting to see in people’s studios. Sometimes I have things displayed properly on the walls but you’ll see something that’s on the table or floor or in a stack on a chair and those are ideas in formation.”

An Open Studios highlight for Bresnick was creating a collaborative site-specific installation with Michael Cloud Hirschfeld in the Pirelli Building, the culmination of conversations and ideas the two artists had shared. Bresnick appreciates the access to “a neutral space where two artists can come together and generate a third way or another set of ideas. It’s a rare opportunity to have space to do that without engaging in a long lease or a lot of expense. But you have to be ready to go, like a military operation — 24 hours and bang it out. That for me was one of those times when something beyond my own work has been generated by the process.”

Energizing neighborhoods

The energy of CWOS extends into the neighborhoods around the studios and Alternative Spaces. In 2003, the Alt Space at 25 Science Park was complemented by temporary outdoor sculptures and interventions nearby, along the newly finished segment Farmington Canal trail.

In 1999, CWOS’ second year, artist Stephen Grossman coordinated the use of the Old Yarn Shop space on Orange Street — now home to Central Steakhouse — as an alternative space. “It was really bombed out. We could only occupy the perimeter of the building because inside it was too dangerous and unlit,” recalls Grossman. “You had the sense of being a pioneer in a vastly devastated space.”

There were several alternative space locations in the Ninth Square that year rather than one big space. (In 2000, Artspace secured use of the Smoothie Building as the first large-scale alternative space.) According to Grossman, “It energized the whole neighborhood rather than a singular building. There was a sense of going inside and outside as a visitor. At the time, the Ninth Square was pretty empty so it really changed the neighborhood, which was somehow a little more exciting than changing a building.”

Stephen Grossman’s ‘Collaboration with a Wall’ at the old Yarn Shop was one of the installations at the 1999 CWOS that enlivened the Ninth Square (photo courtesy the artist).

Grossman, who has created public art sculptures in The Lot both in conjunction with CWOS and in a separate Artspace-backed project, says, “I’ve always hoped there would be more of that mixed in with Open Studios because it creates a more diverse experience and brings it right out into the public.” By having a range of elements — public art outside or in windows visible 24/7, site-specific installations in alternative spaces and the conventional open studios and display of work in alternative galleries — “each piece is enriched because people see art in a more varied context. It makes it more of a festival.”

With all these other elements included, is the name “City-Wide Open Studios” perhaps a misnomer? Rita Valley doesn’t think so. “A studio can be almost anything. It can be a laboratory for creation. It can happen on a street corner, or at a subway stop or in your living room,” she says. “The idea of providing a temporary studio makes a real nice brewing pot for things to happen, things that might challenge the artist, too.” It is an opportunity, according to Valley, for artists to push their limits in a public venue.

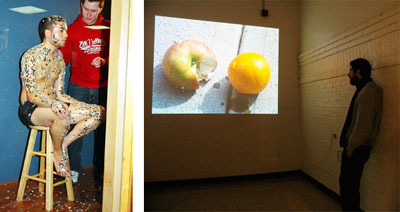

Many artists use the Alt Space as a laboratory for experiments, including a performance by Matthew DeLeon (right, photo by Rashmi Talpade) and a projection by TriFocal Projects (left, 2004, lk).

“The challenge of not only Open Studios but of all art is how to reach out to an audience you don’t have, to get a new audience,” says Steve Grossman. “Seeing some little kid walking down Chapel Street who’s never had an art experience relate to something [in The Lot] — it’s great when it happens.”

Journalist Hank Hoffman has reported on New Haven art, music and culture for the New Haven Advocate, in his blog Connecticut Art Scene and other publications. He has been covering City-Wide Open Studios since 1998.

Photos from the City-Wide Open Studios archives and individual artists. We have credited the photographer and artists pictured whenever possible. If you can help supply missing information for our captions, please contact us!